The product of over six decades of fruitful collaboration, Why? by legendary English director Peter Brook and French playwright Marie-Hélène Estienne is many things: a fanciful reimagining of the birth of theatre from the spirit of boredom, a playful comparison of the methods of Stanislavsky and his lesser-known but equally influential contemporary Vsevolod Meyerhold, a harrowing retelling of the martyrdom of Meyerhold and his wife, eminent Russian actor Zinaida Raikh and, woven throughout, an inquiry into why we do theatre.

“Why?” It’s a question familiar to anyone who has ever schlepped a set through the subway or spent food money on costumes and rent money on rehearsal space. It’s a question that plagues us when our show closes and nothing survives but a few online reviews and a grainy video. When we see our colleagues in film and television landing distribution deals. “Why?” Or better yet, “What on earth are we thinking?”

Why do we give our lives to the theatre?

Do we ‘give’ our lives to the theatre?

Isn’t it the theatre that gives us our life?

Haven’t we a need to be touched by something that gives life a deeper meaning?

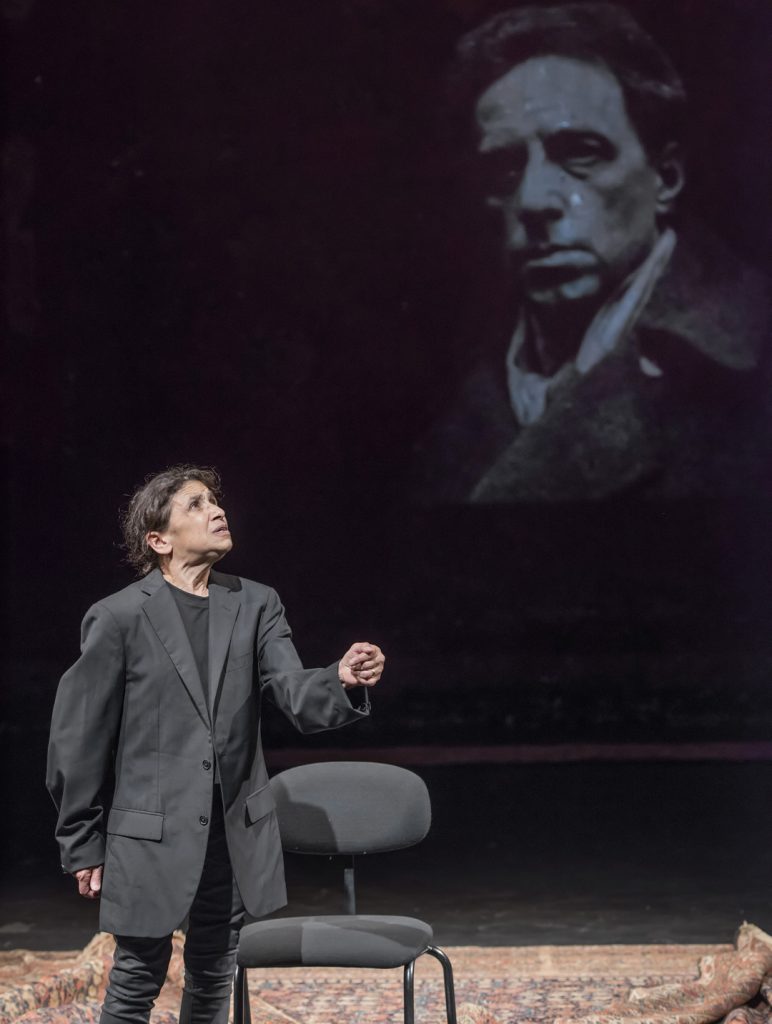

These lines, passed like juggling pins between masterful actors Hayley Carmichael, Kathryn Hunter, and Marcello Magni to evocative piano music by Laurie Blundell, are probably the closest the play ever comes to answering its own question. Clearly, Brook and Estienne want us to answer it for ourselves.

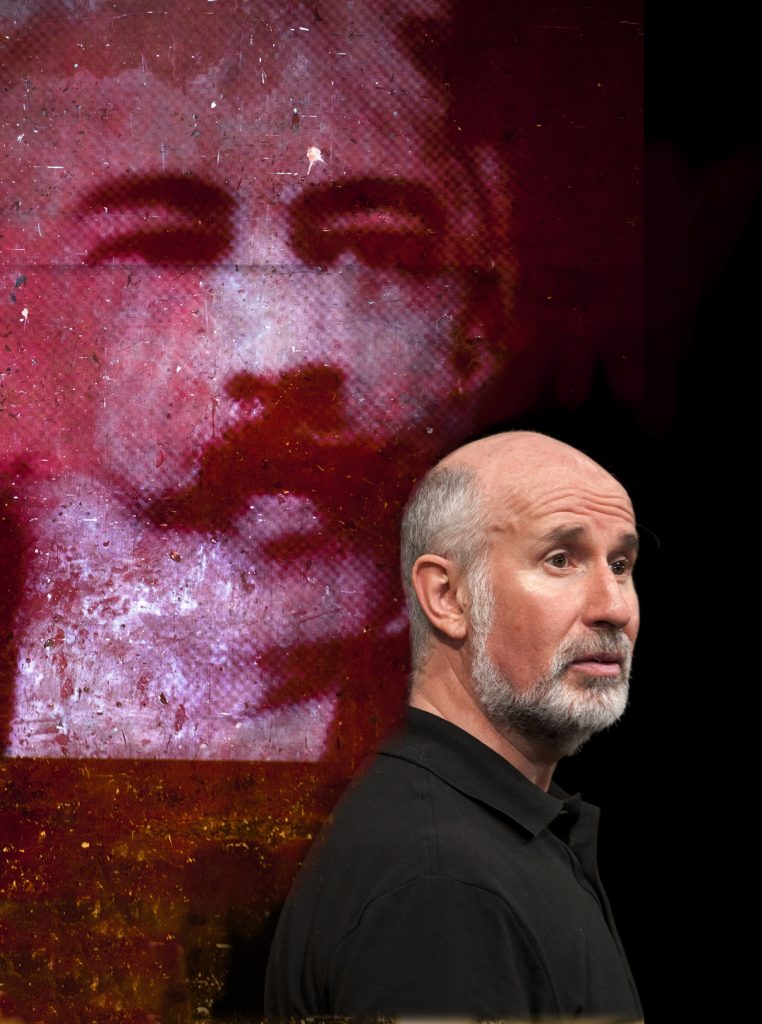

And so, rather than simply write a review, I decided the best way to capture the spirit of Why? was to interview two writer/director/actors who also attended the play: Coleen Shirin MacPherson, whose stage adaptation of Szymborska’s poetry just closed at La MaMa, and Joshua Crone, editor of Reviews from Underground.

Despite the minimalist set and small cast, Why? is strongly visual. What’s an image that sticks with you? And what did you take from it?

CM: The image of Meyerhold’s coat is the most striking for me. Meyerhold was imprisoned in the sinister Burtiky in 1939, and a fur-lined coat miraculously arrives for him. After the verdict comes that Meyerhold has been a traitor to the party, after we learn there was a trial with no lawyer, but only accusations and more accusations, he is sentenced to death. There is this image of the ice-cold morning in the prison courtyard, and Meyerhold is brought out wearing his warm coat. He is shot once in the neck. The actors tell us that: “The coat is kept but the corpse is thrown into the communal grave.” This was such a strong moment for me, in that we just witnessed three actors, simply putting on and taking off an over-sized coat while telling the story of Meyerhold’s martyrdom. Are we to believe that the actors in front of us, here today, are all symbolically wearing Meyerhold’s coat?

JC: I have to agree. The strongest image was the one at the end, of Meyerhold’s execution. The actors paint it in words first: the cold courtyard, the warm coat, the cold barrel at the back of the neck. Then they sit there in silence, three actors in three chairs, looking at the audience and wondering why. It seemed like ages before someone in the back finally started clapping. On a theatrical level I was impressed by the sincerity of the actors. There was no forced pathos, no phony gravitas, just genuine consternation, a sincere desire to understand why, to make sense of that brilliant career in the theatre and its miserable end. Why is the theatre worth living and even dying for? On a personal level it made me ask the same question.

The text ranges all over, from the seventh day of creation to the day of Meyerhold’s execution. Which line or passage spoke to you directly? What did it tell you?

CM: After the play I found myself recalling the line: “Art is to reality as wine is to grapes.” For me, as a theatre-maker and an idealist, I connect to this idea that reality needs to be re-imagined through art in order for us to live with it, wrestle with it, and ultimately, transform it. We focus on Meyerhold’s revolutionary theatre—a theatre that rejected the old ways and magnified life in order for us to see it, a legacy of the theatre we see today. There was a line from Charles Dullin’s reaction to seeing Meyerhold’s play performed in Paris that struck me: “My attention was drawn toward the stage the way a believer in a cathedral is drawn towards the choir.” This reverential quality that Meyerhold’s theatre had, outside of religion and yet reaching for a spiritual dimension, is something I believe we must hold onto, what Brooks calls holy theatre.

JC: One line that really spoke to me came from Meyerhold: “The path to simplicity is not easy.” Historically speaking it was part of an abject apology to the Russian people. He’d been accused of formalism, a grave accusation at a time when social realism was state dogma. His revolutionary experiments may have been welcome in a time of revolution, but now the Party wanted stability and simplicity. Historical irony aside, I think there’s a great lesson in that line. As artists we progress from naive simplicity to self-conscious complexity and—with luck and hard work—back to a simplicity enriched by technique. I think that’s what Picasso meant when he said: “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.”

Meyerhold said “Theatre is a very dangerous weapon.” Is that still true today? What’s the most “dangerous” play you’ve seen lately? And what can be done to increase the danger?

JC: Meyerhold’s theatre was literally dangerous. It contributed to the revolution and, by extension, to the death of tens of millions. I think that needs to be kept in mind when portraying him as a martyr. It’s a point the play never makes explicitly: When a supporter of the Reign of Terror ends up on the guillotine, who’s to blame? In any case, I don’t think the theatre is politically dangerous today. It preaches to the choir. Plays like In the Penal Colony, A Strange Loop, and Skylar would be dangerous if they played to a mixed audience across the political spectrum. But when would that ever happen? Personally, I’m more interested in the theatre’s ability to incite an inner revolution, to change the way we see ourselves and each other. The most dangerous play I’ve seen lately in that sense is Frank McGuinness’s Someone Who’ll Watch Over Me. To increase the danger we need only step outside our ideological comfort zones and meet the “other” in no man’s land. Or we can bunker down and try to be dangerous in the Meyerholdian sense. Why? shows where that can lead.

CM: I think theatre does have the potential to be a very dangerous weapon—but, this rarely happens. I think theatres are under a lot of pressure and the creative process is often so compounded for time, that real risks rarely happen in the rehearsal room. The need to make money is a dangerous thing in itself as it leaves artists and theatres complacent and at the mercy of the financial department.

But setting this aside, I do think theatre can be a dangerous weapon today, and many artists and theatres transcend the barriers by speaking about the present moment in new and daring ways. I think Belarus Free Theatre’s Counting Sheep, which I saw at the Vault Festival in London last year, elicited danger. What made this dangerous was the fact that we were immersed directly in the revolution itself—the audience was divided between “protesters” and “observers” during the Kiev uprising of 2014. You eat, you waltz, you create barricades and wave flags, you carry the dead, all while seeing images of Putin and troops encasing Ukraine even further. And this is happening today. This revelation of the present moment is what makes it dangerous and real and alive for an audience.

Another play that I recall would be Ophelia’s Zimmer, written by Alice Birch and directed by Katie Mitchell at the Royal Court (co-created at the Berliner Ensemble). This was a re-writing of Hamlet, so that the audience focused solely on Ophelia throughout the landscape of the play. She sits, she stares out, she throws the flowers away, repeating gestures, while the men appear in a box upstage and are revealed through sound (Foley) until the final moment when she slits her throat in an act of revolt and the stage fills with water and with her blood. A revelation towards a woman’s world.

How can the theatre be more dangerous? I would tell artists to create for the current moment. Take risks not for their own sake but with vision and a personal connection to the subject. Create with your whole self.

In his classic book The Empty Space, Brook divides theatre into four categories: the deadly, the holy, the rough, and the immediate. Which do you aspire to and why?

CM: The holy theatre. I feel the closest to the kind of theatre that makes the invisible visible, revealing hidden truths about humanity—a visual and visceral theatre, a metaphoric space that launches the audience’s imagination. I definitely don’t see theatre working that tries to represent reality exactly as it is. Realism can be a real trap; can we actually represent reality anyways? For me, the theatre’s power is in its ability to help us dream and imagine, and in a room full of strangers at that.

At the Lecoq school we would work through improvisation every day. Through movement we search for a truthful moment, a truthful emotion on stage and develop our acuteness to observe the world around us for inspiration and to observe what we see on stage. If what we see in the improvisation is “true” then the act of theatre creation was actually unfolding before our eyes. This “true” is a kind of poetic transposition, for the theatre space is always lifted. These are the moments we all yearn for in the theatre in order to put a pause on life.

We all live, we all die, we all experience loss and love and pain and heartache of all kinds, and I think this is what excites me about the theatre and how it brings people together no matter who you are or where you are from. It allows us to see with clearer vision.

JC: I’d like to reach the holy, but through the rough. Drama began with a bunch of dancing drunks with leather phalluses and from there it made a beeline for the sublime. I think the sweet spot is somewhere in between. Or, since stasis is the death of drama, it’s in bouncing back and forth between heaven and earth. Come to think of it, that’s pretty much what Brooks has in mind with his “immediate” theatre, and Why? is a prime example. My upcoming play The Journey is half comedy, half ayahuasca ceremony, so it bounces up and down like a wacky ball. The guiding principle in alchemy is “As above, so below.” I try to apply that to my work, to reach the divine through the mundane.

Why do you do theatre?

JC: I wish I knew. Maybe it’s a higher calling, or a substitute for religion, or a pointless compulsion. Maybe it’s better not to know. All I can say for certain is: I’m miserable when I don’t do theatre.

CM: Today I took part in a ritual at the beginning of a new rehearsal process of a play here at Toronto’s Factory Theatre (Trout Stanley by Claudia Dey, directed by Mumbi Tindyebwa Otu). We were asked to bring in an object that reminded us of why we do theatre. These objects would then be part of an altar in the rehearsal room and later the objects would find their way into the set as a constant reminder of our journey as theatre-makers. A ritual set off by playwright Djanet Sears. My object: a thuya wood box from Morocco with a secret compartment. I feel this box encompasses my “Why” because it is so mysterious. What is in the box? What is hidden? Can it open? Within the box are: a stone from Cairo, a bookmark from Prince Edward Island, a coin from Iran and a perfume bottle from my Grandmother’s drawers full of trinkets.

I could tell you what these objects are, their hidden stories, but perhaps this is a play in itself. The stories themselves are the answer to why I make theatre. But more: I make theatre because I want to ask difficult questions and confront the incomprehensible, because I want to connect the present to the past, because I want to give life to the invisible, to speak to ghosts, to resurrect buried truths and to find a truth hidden deep within myself.

There is not an easy answer to this and there isn’t only one, and maybe this is why Peter Brook, at the age of 94, full of years of wisdom, full of years of creating theatre with pure storytelling, does not want to answer this question. Why? puts the question onto the audience, it makes us pause and wonder. It is the question, the constant “I don’t know,” as the poet Wisława Szymborska would say, that keeps us on this journey.

Why? is running at Theatre for a New Audience through October 6. For tickets and information visit tfana.org. You can follow Coleen Shirin and her company Open Heart Surgery on Instagram at @coleenshirin and @OHsurgerytheatre.